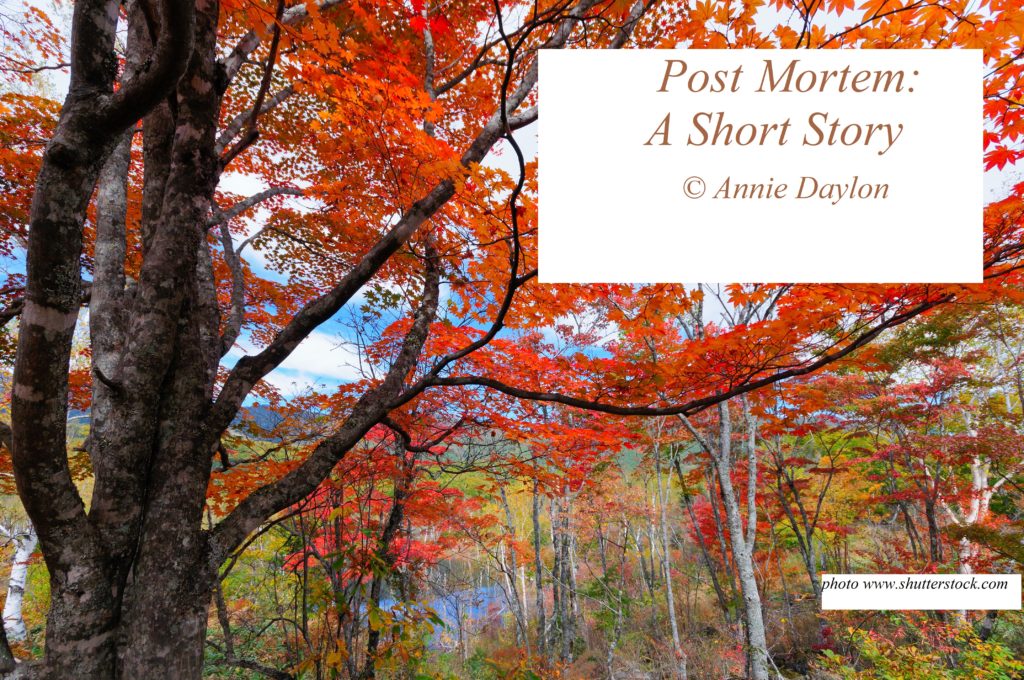

From my collection Passages, an autumn story for the autumnal equinox. Enjoy…

© by @AnnieDaylon

Isadora was not willing to renege a lifetime of promise. For years she had planned, scrimped, and saved and now, at last, opportunity was here. She sprinted through the autumn woods, tendrils of silver hair streaming behind her. Every few steps, she let out a delighted laugh. What a sight she must be! An octogenarian in a full-length, black-velvet skirt, with a bulging shoulder purse hammering her titanium hip. And yet, she was dashing along with the agility of an adolescent doe.

As she neared the clearing, she slowed her pace and kept her eyes down. What if the cabin wasn’t there? For a few seconds, her mind flirted with the extermination of hope and her body responded by coming to a standstill. A sense of fragility imbued her and she felt as one with each crisp leaf she had just crushed beneath thoughtless shoes. With heart and hope plummeting, should she go on?

Overhead, the call of bird and whoosh of wing distracted her. Isadora’s lips curved into a smile. Canada geese. Bidding their annual farewell. She took a deep breath. Wood smoke. A comforting aroma. Emboldened, she raised her head and instantly clapped her hands in glee. It was there, all of it: the old, log cabin with its red-brick chimney; the faded, inebriated-looking Adirondack chair; the window boxes with their peeling, green paint and stubborn, pink geraniums. Still blooming. Amazing.

She felt content to linger, to stare, but a blast of cold air slapped her, snaked under her billowing skirt, and caused her whole body to shudder. She clutched her purse to her chest and rushed to the rickety porch steps which whined in protest as she climbed. Sidling up to the door, she knocked. A timid knock. She waited.

As Isadora hovered, another gust of wind sent leaves flying. They swirled and spiralled around her and fell at her feet in a mosaic of ochre, red and brown. Autumn. She grimaced. To some, autumn meant renewal. To her? Her whole life, she had watched as autumn approached, encroached, and retreated, taking all living things with it.

Isadora recalled her first encounter with autumn’s cruelty. She had been playing outside and a single oak leaf, which had magically turned from green to yellow, had fluttered down and landed on her shoe. She snatched it up and ran home, intent on show-and-tell with Mommy, by the fireplace. But an eerie sound emanating from the house caused her to hesitate, to peer through a side window instead of entering. Her eyes widened and flooded as she watched her father fall to his knees, wailing, at her mother’s bedside. Interspersed with his cries, were words of regret and apology. Hard to decipher but, within seconds, the young Isadora understood. Doctors cost money. Her father had no money and, because of that, her mother, like the leaf in her hand, was dead.

That autumn, Isadora watched leaves fall, one by one, until none remained. All winter, she listened as naked trees moaned, echoing her pain. She was alone. Shuffled from one relative to another. Abandoned by a devastated father who knew nothing of raising a three-year-old girl.

Every subsequent autumn, as leaves rained to the ground, regret haemorrhaged through her pores. If only she could have changed things. Doctors cost money. If only she could have given her father money. Somehow, she always felt that she could have done something. Should have done something. But she had failed.

As she stood on the porch now, waiting, Isadora’s hope began to dwindle once again. She repeated the knock. Still no answer. Anxiety crept into her body, causing her to tremble. She let out a sob, formed her fingers into a fist, and pounded the door.

This time the door squeaked open and a tiny girl, a mere waif, stood there. Isadora gasped and recoiled. When she caught her breath, she leaned forward. “Hello,” she said to the bedraggled child who was hugging a filthy, hairless doll.

The little girl was silent.

Isadora held out the purse.

The child’s eyes popped wide. “Mommy’s purse,” she whispered. “That’s Mommy’s purse.”

“Yes.” Isadora opened the purse, displayed its contents, and closed it again. “I kept it all these years, filled it, just for you.” She placed the purse at the child’s feet. “You know what to do?”

The child nodded slowly. “Doctors cost money.”

A tidal wave of realization flooded through Isadora. She had done it. For a few seconds, she stood, frozen. Then, in measured motion, she turned and headed down the steps. At the bottom, she paused and looked back.

The little girl, waif no more, was still standing there. Her dress, new and pink and velvet, matched that of the pristine, porcelain doll she carried and her waist-length, glistening blonde hair was topped with a pink velvet bow.

The two exchanged no words, only smiles.

Isadora walked away, gradually picking up her pace until she was skipping along the woodland path. Deep within her, sad memories began to disperse, dropping away one by one, like the falling leaves around her. Soon those recollections were gone, replaced by images of a happy little girl, learning, laughing, and singing, at her mother’s side.

Isadora returned to the starting point of her journey—the funeral parlour—and slid through the front  door. She entered the viewing room and floated for a while, staring at her body, resting in its mahogany coffin. She sighed in contentment and slipped back into place.

door. She entered the viewing room and floated for a while, staring at her body, resting in its mahogany coffin. She sighed in contentment and slipped back into place.

Cradle issues resolved, she was ready for the grave.

My best to you,